2026

2025

![]()

![Alan Charlton and Liam Gillick Liam Gillick and Alan Charlton, Alfonso Artiaco, Naples, 2025]()

![Alan Charlton and Liam Gillick Liam Gillick and Alan Charlton, Alfonso Artiaco, Naples, 2025]()

![]()

![Continual Discussion Platforms & Endless Discussion Platforms, 2025]()

![Continual Discussion Platforms & Endless Discussion Platforms, 2025]()

![Concise Division, 2025]()

![Performance Measurement, 2025]()

![Liquid Development, 2025]()

![Cornered Development, 2025]()

![Meantime Production Cycle, 2025]()

![Meantime Production Cycle, 2025]()

![]()

2024

![]()

![]()

2023

![]() 1995, Erasmus is Late, Book Works, London.

1995, Erasmus is Late, Book Works, London.

![]()

1995, Ibuka!, Kunstlerhaus Stuttgart.

![]()

1997, McNamara Papers, Le Consortium, Dijon & Kunstverein in Hamburg.

![]()

1998, Discussion Island/Big Conference Centre, Kunstverein Ludwigsburg, Orchard Gallery, Derry.

![]()

1998, Ein Rückblick aus dem Jahre 2000 auf 1887, Galerie für Zetigennössische Kunst, Leipzig.

![]()

2000, Liam Gillick, Okagon/Lukas & Sternberg.

![]()

2000, Five or Six, Sternberg Press, Berlin.

![]()

2002, Literally No Place, Book Works, London.

![]()

2002, The Wood Way , Whitechapel Gallery, London.

![]()

2004, Underground (Fragments of Future Histories), Import (mfc-michèle didier & les presses du réel), Brussels.

![]()

2005, McNamara Motel, CAC Malaga.

![]()

2006, Liam Gillick and Lilian Haberer, Factories in the Snow, JRP|Ringier, Zurich.

![]()

2007, Proxemics; Selected Writings

(1988-2006), JRP|Ringier, Zurich.

![]()

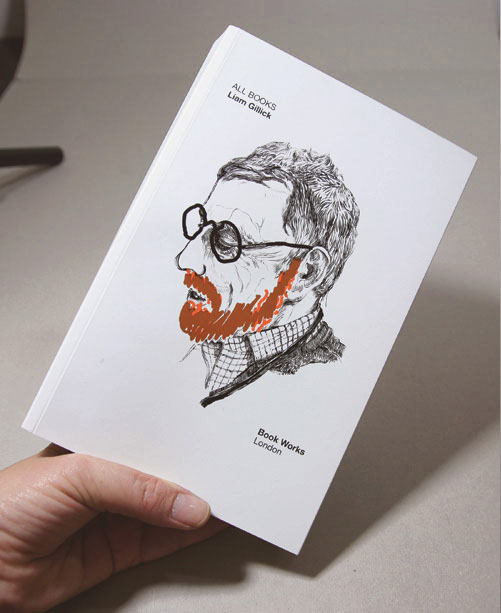

2009, All Books, Book Works, London.

![]()

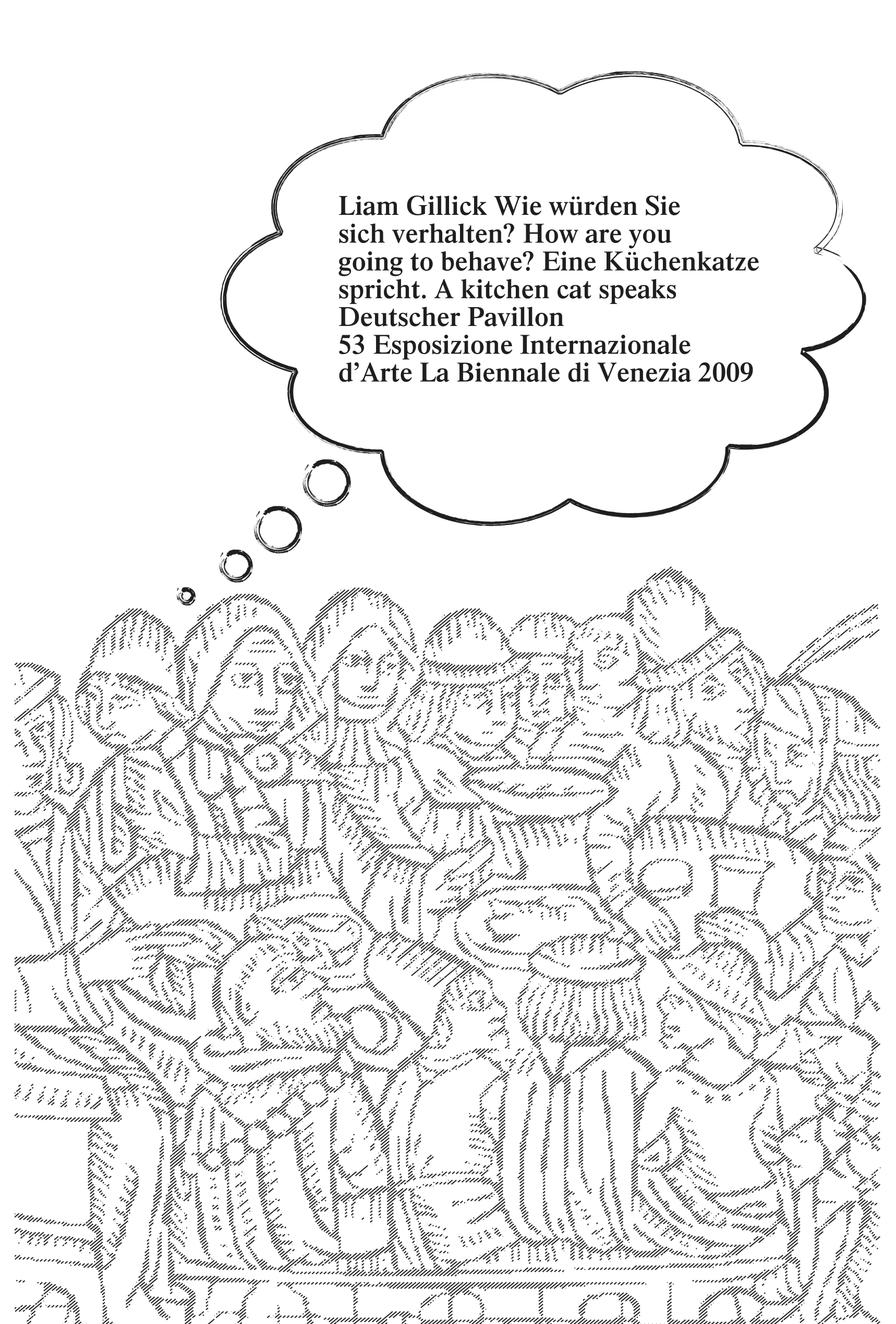

2009, Liam Gillick: Deutscher Pavillion La Biennale Di Venezia, Sternberg Press, Berlin.

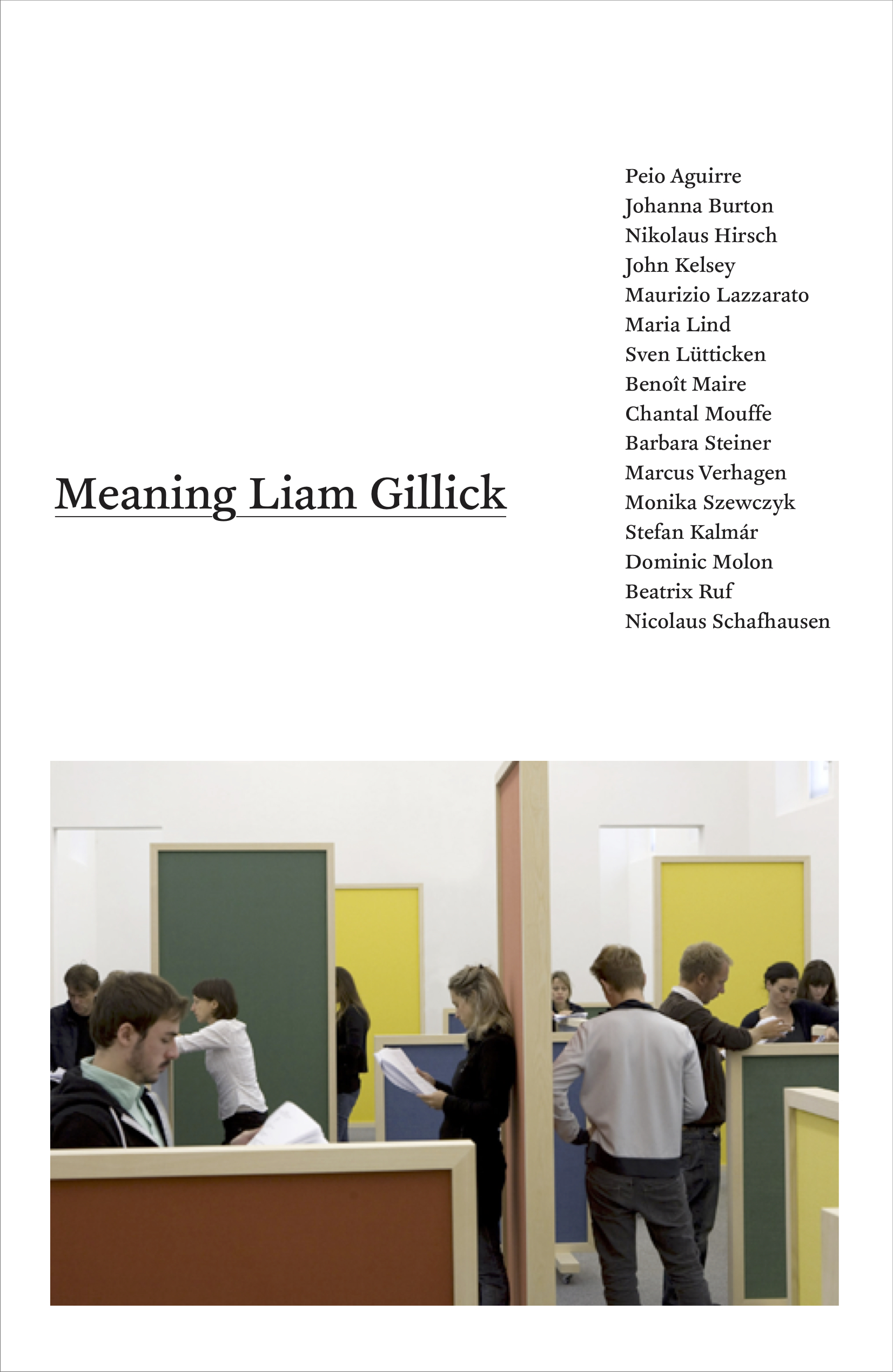

2009, Meaning Liam Gillick, MIT Press, Cambridge.

2010, One long walk… Two short piers… Kunst-und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, Snoeck Verlag, Koln.

![]()

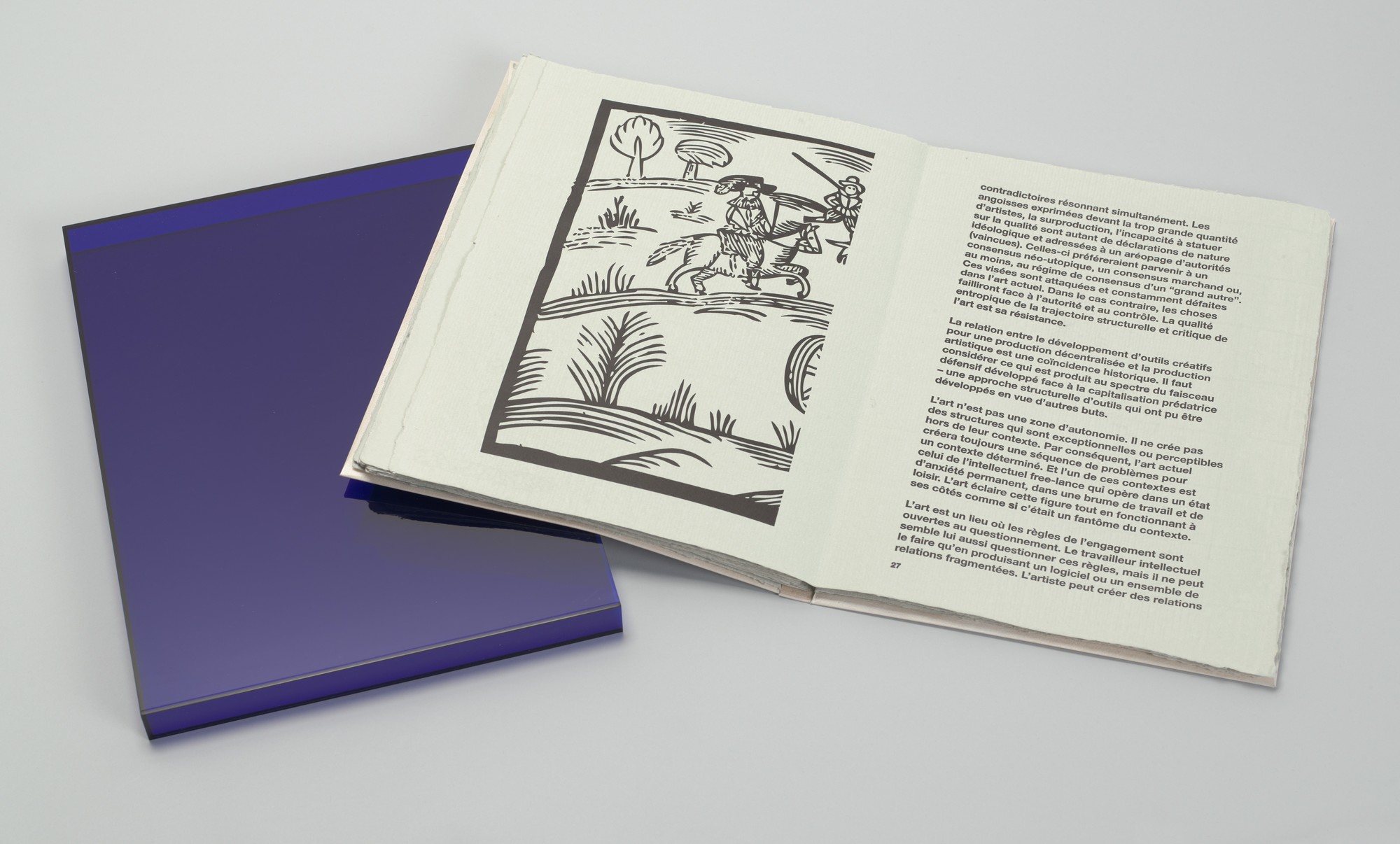

2010, Pourquoi Travailler? Three Star Books, Paris.

![]()

2011, Liam Gillick and Lawrence Weiner: A Syntax of Dependency, Mousse Publishing, Milan.

![]()

2014, From 199A to 199D, JRP-Ringier/Bard Hessel Museum/Magasin.

![]()

2016, What’s What in a Mirror, Dublin City Gallery

The Hugh Lane.

![]()

2016, Campaign, Museu Serralves, Porto.

![]()

2016, Industry and Intelligence: Contemporary Art Since 1820, Columbia University Press , New York.

![]()

![]()

2017, Workplace Aesthetics, CAC, Vilnius.

![]()

2018, There Should be Fresh Springs, Gallery Baton, Seoul.

![]()

2019, Schreibtischuhr , Meyer Kainer, Vienna.

![]()

2019, Half a Complex, Hatje Cantz, Berlin.

![]()

2020, Standing On Top of a Building, Madre Museum, Naples.

![]()

2021, Between Fable and Parable, Ora et Lege

Broumov Monastery, 2021

![]()

2021, Like a Moth to a Flame, OGR / Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo / Corraini Edizioni, Torino.

![]()

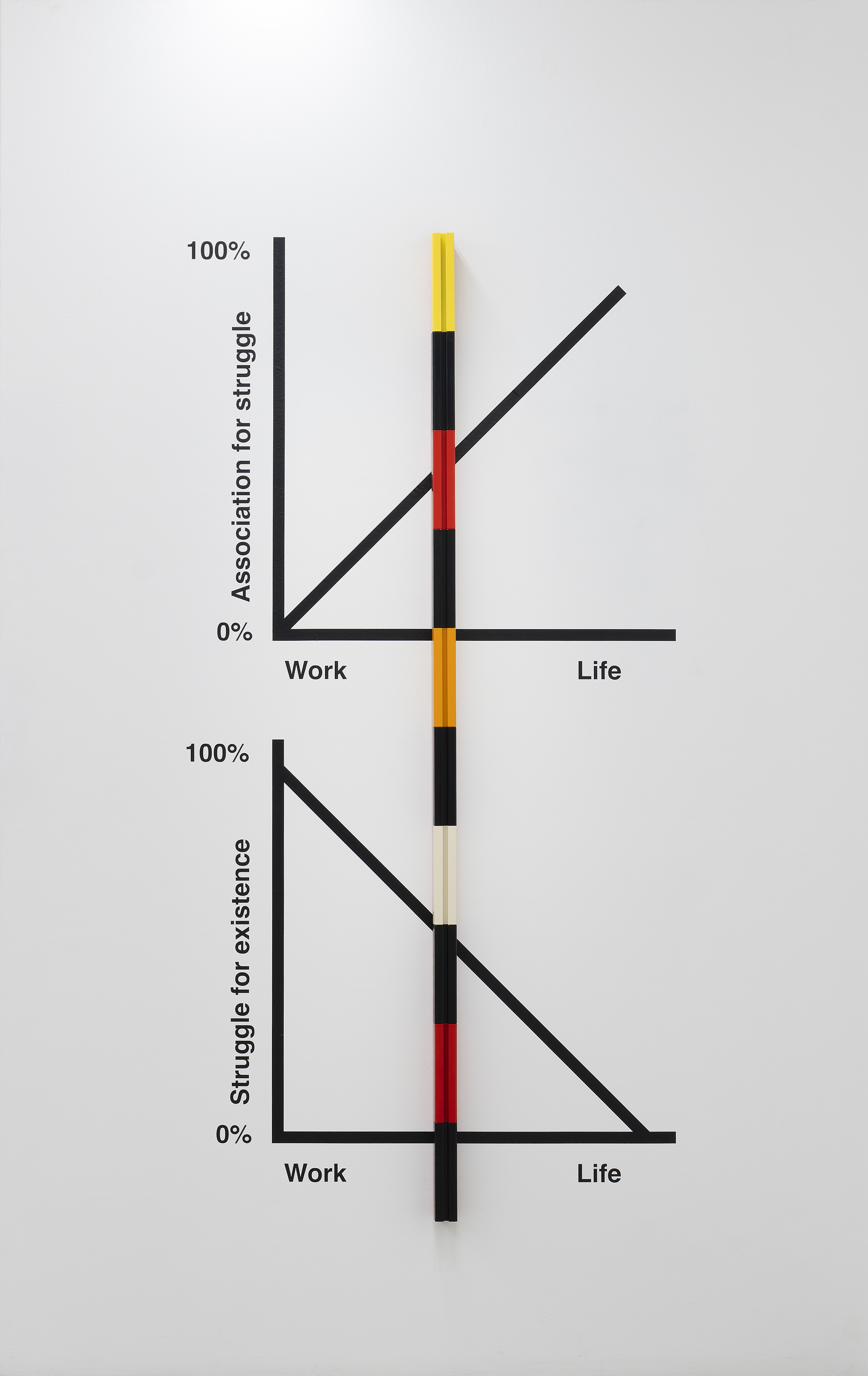

2021, The Work Life Effect, Gwangju Museum of Art.

![]()

2022, Farbe ist Programm, Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn.

![]()

2022, ‘A Max De Vos’, Bozar, Brussels.

2023, Liam Gillick, Filtered Time, Pergamon Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

2025, Liam Gillick, A Variability Quantified, National Gallery of Canada, Fogo Island Arts.

What do you represent?

Liam Gillick

Published in Tell me about yesterday tomorrow: A Book about the Future of the Past, NS-Dokumentationszentrum München, Hirmer Verlag, Munich, 2021

It is with a somewhat heavy heart that I Google the words “Fredrick Adolf Reinhardt: What does this Represent, 1946”. For those unfamiliar with the cartoon that shows up in the Google search results, it was produced by the American abstract artist “Ad” Reinhardt for PM newspaper in New York. It was one of many cartoons he made about the question of modern art and its supposedly disturbing effects upon established values between 1942 and 1947. The cartoon is divided into two parts. In the upper section, we see a man tilting towards a hanging panel that carries cuneiform script. He has turned towards the viewer and wears a hat, a business suit and a wide eyed grin that implies we will share in his mockery of this unintelligible nonsense. “Ha Ha. What does this represent?” he moronically exclaims. In the lower image, the hanging panel has been transformed into a sketchy likeness of an abstract painting with something of the style of a Kandinsky painting. The painting wears a scowl drawn onto its right hand side from which a nose and an accusatory pointing arm and finger have knocked our mocking viewer sideways with the retort: “What do you represent?”. Underneath the drawings is the sentence: “A painting is not a simple something or a pretty picture or an arrangement, but a complicated language that you have to learn to read”. While this cartoon is somewhat famous it is less often reproduced alongside its equally important accompanying panel. This second panel turns attention to what we might call “the obligations of the viewer.” The now confused looking man in a hat finds a rope placed around his neck. He is clearly the man from the first panel. The rope is held with a ring enclosing a dollar sign. His eyes are reduced to twin vortexes of confusion and resignation. Around his head are the words: “Rich Man? Poor Man? Beggar? Indian Chief? Progressive? Good Guy? Trade Unionist? Professor? Reactionary? Wise Guy? Money Grubber? Dope?” And underneath is the following sentence. “After you’ve learned how to look at things, and how to think about them, clear up the problem of what you personally represent...”

Self-referentiality in art and related cultural production is structurally critical – meaning it is critical of the structures of art and at the same time it is evidence of critical thinking within the self and in relation to the collective. Self-referentiality demonstrates self-awareness and consciousness of the relative status of that which has been produced. Humans have always made things that sit in wide gulf between function and organized superstition (various religions) and the “art” that results is something in a constant state of negotiation and reconsideration. Of course, some art is also functional and some art is produced in the service of magic, religion, and various consciousness raising structures and still remains art. The functional or proselytizing potential of art always embodies a substructure of self-conscious produced for various, often contradictory, reasons. Which is why we are capable of going to a museum which holds paintings of crucifixions, poor people eating dinner, rich aristocrats with heavy eyelids, and blurry pictures of trains steaming across viaducts – and are still able to find some common artness in their varied execution. Crucially overlooked in anxious claims to art’s self-regard is that artists also communicate with and develop new languages in relation to each other – some arequite indifferent to comprehension or excessive management of desire – attempts to corral and control arts content – and this is something that only a repressive society would want to hinder. A lot of contemporary art conforms to the adage, “artness is the whatness of all art” – to succinctly ruin James Joyce’s rather more elegant “Horseness is the whatness of allhorse”.

“Aquinas and his followers distinguished between the essence of a thing (its “quidditas” or its “whatness”) and its existence, a distinction that the artist must bear in mind to reach beauty in the work of art. We should not forget that: “the epiphany was the sudden revelation of the whatness of a thing, the moment in which the soul of the commonest object . . . seems to us radiant.”1

In the summer of 2020 I made an exhibition in Tokyo. Making use of the phrase Horseness is the Whatness of Allhorse as the title of the exhibition, I wrote:

“Joyce brings animal form to an abstract philosophical concept – testing universal claims with the example of a living thing. There is some irony in this gesture for the process also renders the animal as philosophical abstraction. The phrase Horseness is the Whatness of Allhorse is a permanent reminder of the limits and potentials of art in pursuit of the essential “whatness” of an object in relation to the “artness” of the art work. It is a resolutely modern phrase that is embodied (as a horse), made production values, techniques, effects and affects that allow us to read across art comprehensible and rendered absurd at the same time. It is philosophy brought to the racetrack and tested against the reality of the city and the farm.”

The self-referentiality I write of is not limited to contemporary art or the world that emerged around it. Self-referentiality can be found at every historical phase of human production. It is particularly notable in the making of what we might call the drive to create art, in its broadest sense. In the caves and on the plains, something was produced – often in the presence of others. Think of the process of art in the company of others: the making of marks and the emerging of carved, scratched or painted images as a procedure of unveiling, revealing and sharing in abstract creation. The ancient artist would either produce art to entrance the other, to leave behind a message or produce art as a collectively shared process. To tell stories, to show off and to cleave off the excesses of consciousness, dreams and desires. Processes of play in regard to revealing and emerging are those that take place when we demonstrate the production of an artwork. When we watch an image emerging at the interface of a human and a surface, the process of emergence and that fact bind and unbind the producer and the witness. An ancient wanderer might come across artistic messages in the form of images and signs upon the landscape and read them in a way that is non-linear, but also one that requires a recognition that another human has already passed this way and wants to leave behind a demonstration of skill or ingenious design merely to entertain the other. In a related way, the encounter with an ancient artwork at the moment of production required a recognition that something was about to be produced by another human and within the nuances of that production, one might find moments of recognition and alienation from the producer of the work at the moment of execution. It is this process of simultaneous recognition, estrangement and revelation that provokes a quality of interest in the apparently non-functional artistic production of another human. This does not imply there is no “use” in art. There is a big difference here between function and use. All art has some kind of use value. Even if there are moments when the ability to read across every nuance of an artwork might require an immersion into the points of emergence, reference and lack that are embodied within it. Art is partly about recognition and that can also be powerfully expressed negatively as “I do not understand this thing,” “This thing makes me uncomfortable” or “This thing is making fun of me and my values.”

Nationalistic and neo-fascist structures today are currently fighting a “culture war” against forms of subjective art and cultural assertion that are often inherently self- referential and can require complex reading, including music, literature, and fashion – purely because these threaten the pseudo-universalizing desires of the existing dominant culture in advanced industrialised countries. All complex expressions of creative subjective assertion contain elements of self-referentiality. It is required in order to speak within many layered alienated groups and refine motifs towards the creation of new languages of expression and therefore mount endless challenges against the boredom provoking anti-human quality of approved art forms – which are incapable of expressing the thoughts and ideas of alienated groups. All complex expressions of self-referentiality are against the “transparency” desired by neoliberal political structures. All attempts to quash art forms that are viewed as incoherent and self-referential signal that one is living in a society that requires the establishment of a “them and us” in order for the dominant culture to keep its dominant position. The cartoon by Reinhardt may be by a white man and drawn in the 1940s in the nascent Empire of the United States, but its message, that by reading apparently self- referential forms and attempting to understand them we must also ask who we are, remains a foundational aspect of why we must protect cultural forms even when they make us uncomfortable. This is not the same as alt-right claims for “free speech”. We know that such claims are quite the opposite to what they intend. Free speech pleas are generally invoked to protect the “speech” that seeks to hinder or obscure forms of cultural expression that make the speaker uncomfortable – to shout down and drown out nuance and difference. Claims that free speech is being suppressed proliferate when others develop new languages to describe oppression – and that includes artistic production – and those new languages appear threatening to the established “order”.

All authoritarian governments attempt to introduce the notion that there is a decadent art that is self-obsessed and self-referential – and pitch that against “universal” values of representation that are inherently evading unique, different and new human stories, experiences, techniques and languages. The creation of semi-autonomous worlds of creative habits and codes threatens the oppressive pseudo-universalism of the dominant class. And at the same time summons worrying implications for those who attempt to instrumentalize art and reduce it into a force for “social good”.

So what of those who are anxious to achieve the watchword of advanced bureaucratic liberal political structures – particularly in Europe – accessibility. Let us first deal with the political and technical aspect of this word. Ensuring accessibility in racial, economic and class terms is a never ending task that requires clearly articulated political outcomes. But when we think of accessibility in relation to artistic content – those who worry that art is too self-referential to allow access to its strange codes and reference points, then we have a problem. Those who worry in this regard often believe that art has a potential to change things and it also has the duty to educate and improve humans. No study of art history could be made and result in such assumptions. Neither the reason it was made in the first place nor how it was produced, received or understood. The twentieth century in particular was driven by art that was evasive, petulant, super-subjective, hard to read and often dismissive of the notion of art and artists as good citizens. It is arguable that the first decades of the twenty first century have invoked new demands that artists are indeed good citizens and art does hold the potential to change things. Encountering art is to come face-to-face with a series of questions about who you are in relation to this thing, structure or affect. There are many questions to be asked of the surrounding context, by artists and non-artists alike – who makes the decisions about what is shown where and who can gain access to it – and this is where the focus of attention should be. It is the “art world” as a surrounding structure of administration that often makes over reaching claims about arts potential and the curator or administrator’s unique ability to break down the supposed barrier between art and the poor alienated public. To over-reach art and create an imaginary ethical demand upon it to satisfy the requirements of an increasingly large bureaucratic sphere of administration is as destructive to human self-realization as those who attempt to universalize an approved art that negates all of its self-referentiality in favor of an inoffensive neo- nationalist consensus.

I accept that contemporary art is a matrix of paradox – that’s what makes it interesting and a fractured mirror of our time. In this regard it sits in a strange symbiotic relationship to philosophy and cultural theory. Contemporary art is a product of philosophy and theory and feeds it at the same time. Modern philosophy has always looked at human artistic production as a way to interrogate new forms of human consciousness and desire. But art does not always look at philosophy for the same reasons. It looks to philosophy and theory in order to find new ways to disrupt or confirm the very structures of thought that it feeds off. Contemporary art is applied philosophy that seeks to find form for questions about reality, existence, and the human potential, and to create languages that account for contradictions and lacks in the theoretical framing of existence. In order to do this, art tends to make reference to other art. Trying to imagine an art that could do otherwise results in an easily dismissible philosophical paradox. This does not mean that all contemporary artists are students of philosophy nor that the ones who are well read even understand or apply philosophy in a logical or effective manner. The two developed together and work off each other with often wonderfully creative or catastrophic results. All contemporary art is rooted in some philosophical aspect that can be described – even if the intention of the artist is to deny that very possibility. And when artists are “good students” they do not necessarily make the most interesting art. Philosophy about aesthetics is sometimes used as a guide for making terrible paintings. Mid- century musings on the culture industry are censoriously twisted into moral frameworks for producing installations in biennales. Neither of these things necessarily advances art or philosophy. There is a productive tension between the art and philosophy. At best, forms of new philosophical reflection and creative acts of art making produce something in the gap of that which is already known and, most importantly, they reflect on what has already been produced and divine new paths. To produce without awareness or reference to that which has already been produced would suggest a sense of delusion that was against other humans. This does not exclude the possibility of deliberately attempting to ignore everything else that had already been produced. That’s the paradox of the contemporary artist.

Nearly ten years ago Dieter Roelstraete quoted Thierry de Duve’s book Kant after Duchamp3 in his essay on a similar theme to this in the art magazine Frieze:

“You descend to Earth. Knowing nothing about it, you are unprejudiced [...] You start observing humans – their customs, their rituals and, above all, their myths – in the hope of deriving a pattern that will make Earth-thought and its underlying social order intelligible. You quickly notice, among other things, that in most human tongues there is a word whose meaning escapes you and whose usage varies considerably among humans, but which, in all their societies, seems to refer to an activity that is either integrative or compensatory, lying midway between their myths and their sciences. This word is art.” He continues to quote a later passage: “these symbols that humans exchange in the name of art must have [...] the undeniable function of marking one of the thresholds where humans withdraw from their natural condition and where their universe sets itself to signifying”. In other, more elegant words still, art appears to have “no other generality than to signify that meaning is possible”. 4

While Roelstraete develops this into a text against both the proliferation of managed expectations around art and the development of a new form of excessively self- referential art – I would venture to develop some more nuanced implications and add them to his argument. Managed expectations about what art can do are supposedly a way of increasing access to an ever more demanding self-referentiality in art itself. Roelstraete worries about whether artists can be “understood”. This is maybe a “natural” problem for someone like Roelstraete who trained as a philosopher, but a strange one to be concerned about. You never know, an art work that could not be understood might render it useless in the back and forth between the confusion of art and the academic practice of philosophy. Yet to police “understanding” would involve a number of philosophically unobtainable developments, and that I am sure he would agree with. First, it would require knowing a limit to understanding and secondly, it would involve finding the border to misunderstanding. In either case “understanding” would require policing and defining. A better position might be to remove the requirement that public funding for art should include a proviso that it is for the public good via its educational potential and secondly take a much more serious look at the political and economic framing of contemporary art’s expansion – namely the rise of the art fair on one capitalistic extreme and the often overreaching claims of various Biennale foundations where good social work struggles to live up to the desires expressed in the catalogue. Any attempt to otherwise police self-referentiality towards better understanding would deny access to new and potentially uncomfortable voices right at the moment when the political drive exists to engage, not only with new audiences, but more importantly, with new forms of production. Truly creative movements are initially hard to commodify and difficult to instrumentalize at the moment of conception. They also tend to feed off themselves in terms of rapid development of ideas within a small group. It is that moment that should be protected and funded. Conforming definitions of intent, understandability

and a limit to self-referentiality into clear terms of production and reception should be rejected out of hand as they will always affect the least entitled creators the most.

1. Rafael I. García León, Reading Ulysses at a Gallop, in: Papers on Joyce 3, 1997, p. 3-8, 8.

2. Liam Gillick, Introductory text to the exhibition “Horseness is the whatness of allhorse“ (June 5 to July 4, 2020, Taro Nasu Gallery, Tokyo, Japan), see https://www.art-it.asia/en/partners_e/gallery_e/taronasu_e/209616 (retrieved on 12 October 2020).

3. Thierry de Duve, Kant after Duchamp, Cambridge (MA) 1996.

4. Dieter Roelstraete, Echo Chamber. Is today’s art too self-referential?, in: Frieze, Issue 148, June–August 2012), https://www.frieze.com/article/echo-chamber (retrieved on 24 September 2020).

Reverse Iconoclasm

Liam Gillick, 2022

First published in Readiness to Protest

Contemporary Activism between Attitude and Style

Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, 2023

An art collector owned a drawing. It was a deceptively simple expression of weakness. A small piece of paper, torn in places, framed so as to hang loosely without a mount. People could not usually remember the details of the drawing, but there were probably a few indecisive marks on the paper, this was part of the point. The marks on the drawing were undoubtably made with a number of drawing implements – oil stick maybe, a bit of pencil. A small piece of paper might have been stuck to the surface. This smaller part was probably a different color to the main drawing and was also torn rather than carefully cut. This art work – with its commitment to non-rational abstraction – sat in some tension to the rest of the collection. It was to be found somewhat isolated, in a private area of the house. Pride of place elsewhere definitely went to rational minimalism, conceptual art and some examples of important monochrome late modernist abstract painting. The art collector had a young son. “What…” the boy wondered “… is the meaning of this art work?” Everything else was clear, in its simplicity or conceptual rigor. One day the artist was passing through the city and came to visit the house. The boy was encouraged to talk to the artist – and teased by his parents to ask the big question. “What…” the boy asked “… is the meaning of your art work?”. The artist was a kind person and liked children – even though he had none of his own. “Why… Can’t you see? It’s a protest against the Vietnam war.”

Protest and art that is recognized and valued as art in its time, begins with an ebb and flow between the deployment and destruction of art in relation to established power. In Europe this documented history starts with internal religious battles within the early Christian church about the representation of icons. Iconoclasm – the destruction of icons – is a permanent feature of religious formations from the beginning of recorded human history and continues to overshadow the development of art and moderate its appearance. John Grammatikos from the early 9th Century is the most cited example of this early desire in the Byzantine Christian world due to the existence of a critical image of him erasing a picture of Christ with a sponge on a stick – while just above we can see a fine drawing of Jesus being offered a sponge drenched in vinegar by a Roman soldier. An act of destruction pitched against a representation intended to prove the necessity of direct visualization. Iconoclasm runs forcefully through European history. Calvin’s iconoclasm lingers in the contemporary aesthetics of of north western Europe and America – in reductive modernism, empty galleries and minimalist interiors. But it also exists everywhere, in all societies influenced by the legacy of organized religions which disciplined and controlled the deployment of images and objects. Art has therefore developed in dialogue with its potential disappearance for all of human history, and in the early modern period in art forms we recognize as functioning as art, it was often disciplined to secrete messages and protests via allegory and symbolism rather than speaking directly. Throughout history art has been the subject of protest and destruction by authority rather than a vehicle for a direct expression of protest against authority. The development of art is not only affected by the legacy of its internal battle over the religious meaning of images and objects but also haunted by the fact that art is a special type of commodity. Uprisings of peasant classes directed against religions, and rulers throughout the same recorded human history led to the destruction of art as a form of protest against its status as a symbol of wealth and power. So we have a double legacy of destruction. A protest against art from within the ruling system. And a protest against art from outside the ruling system. Art was always an object of protest not an agent of protest.

So the idea that art and protest go together is not wrong. The implication, however, that art itself can be a form of protest rather than the object of protest is a contemporary idea. It is an intellectual construction inflected by the legacy of art’s elusiveness. The great art of the ruling elites often carried embedded messages – symbolic, compositional or in terms of narrative allegories. But it was primarily in the service of power and treated appropriately – with reverance and awe or with destruction as a result of uprisings and revolt. Art functions today in forms that reveal the embedded effects of this endless history of deployment and erasure, re-drawing and re-erasure – this is what gives contemporary art its elusiveness, dumbness and hyper-intelligence in equal measure. To achieve this endless elusiveness the corralling of art in the modern and contemporary period has required institutions, critics, curators and theorists to mould and interpret it – effectively to “establish” it within a human centered period of “participatory democracy” and supposedly free it from endless cycles of censorship or empty decadence.

The victory of contemporary art therefore is an escape into a reverse iconoclasm where art and particularly the figure of the contemporary artist – as an idealized contemporary “agent” – finally turns the tables on established power structures. Art now exposes us to the potential of unfettered human creativity and self-conscious displays of industry, intelligence, and resistance in the form of art as protest. If contemporary art is the first form of art in history to free itself from the twin forces of historical destruction, how has its new role and potential as a form of protest been structured? How has it passed from subject to agent. One solution is to look at arts relation to that which is being protested in terms of time.

Contemporary art functions within and without protest in three temporal modes. The first temporal expression operates in advance of conditions to be protested. This is protest that warns and predicts of grim things to come. The second occurs at the moment of the event or within the context of broader protest, specifically or in generally. Here the artist is a citizen amongst all others offering their particular skills of communication and imagination. The third is essentially reactive and expresses forms of protest against a given structure that is already clearly operative and can be defined as operating within a fully established system. In this case the use of art as protest is pitched against grand systems, such as institutions, political structures and the fundamental organization of societies. These different time based expressions of protest in relation to contemporary art can be rethought a little in regard to the differences between exile and dissidence. Exile and dissidence can be cast in terms of time and space. Exile is an exteriority, it is an absence, either voluntary or involuntary from the place of trauma and oppression. It can remain silent – and as an act in itself can be understood on multiple levels of engagement. One form is pure exile via an escape to get on with a new life without comment or agency, the gesture or escape itself being a meaningful action without comment. Exile in this case can be endless. Every waking moment can be consumed by expressions of loss and awareness of exile and this can pass from generation to generation. Dissidence is a different but related state and exists in the recent past, present and near future. An exile may also be a dissident but a dissident is not necessarily an exile. Dissidence also has varied qualities. An “official” form of it can operate with tolerance and encouragement from authority. Alternatively it can be a nagging constant form of aggressive and resistance towards those in power.

The differences between exile and dissidence exist in these three time based relations when considering protest in relation to contemporary art. Contemporary art and protest can be interior and exterior, and expressed in terms that are hard or soft. At one extreme, as with the mildest forms of tolerated dissidence, art and protest find expression within the substructure of politically sanctioned, instrumentalized art. All political systems today that recognize something we might identify as contemporary art, make use of the structures of art, either via direct funding or tacit support, and deploy it towards the expression of some kind of positive protest for or against something. Art in post-industrial economies is instrumentalized against climate change, inequality, poverty and so on. But this instrumentalization is not limited to the richest countries. Every country uses art in some way as a form of official “protest” against general conditions, through the “raising of awareness”. They all assume that art has some power. Particularly that it has the power to express inclusivity, decency, education, creativity and other “positive” human attributes against the climate emergency, poverty, exclusion, and so on. At its lowest level, art as protest as official expressions of sanctioned dissidence can merely involve the simplest addition of a commonly held ethical or moral value to a social media post making reference to any of the above. This is art as sanctioned protest operates in the “simple present tense".

Art as protest as exile is often more nuanced and biographical. Major chunks of modernism and contemporary art are underscored by the exile status of their creators in the story of twentieth and early twenty-first century art. Everything about this work is at some level an expression of exile. Exile finds form in yearning backwards and forwards. A backwards projection upon what is lost and gone and a forward looking rejection of everything that has taken place in the past that continues into the present. As such, exile is a continually disturbed state that produces an excess of memory and a complete rejection of memory in equal measure. At some level all modernist and contemporary art since the First World War has been an expression of exile. A yearning for values that predate industrial killing and a complete rejection of the values in the past that could lead to such a condition. All art of exile is a protest against the failures of the past and a potential reimagining of all the conditions of production and reception of art in the present and future. This is art as protest that operates in the present and points forwards at the same time.

How do we therefore model art as protest after the event? If we accept that dissidence is not necessary from people in exile, it is also true that exiles can remain dissident. These conditions can both exist after the firm establishment of the conditions spoken out against or escaped from. The act of protest is defined and honed by the situation being protested. It reacts strongly against something that has taken place and continues to take place. Art in this case functions with elements of documentary, commentary and tries to unlock the conditions of the present through the construction of new languages and new power formations. In the final temporal stage, art and artists reflect back upon prior conditions and deploy various tools to reshape and re-stage the past. By doing this they build new versions of history and open them up to potential rethinking and reimagining. This is a position that can admit the persona of the exile who has returned. And the dissident who is now recognized as a visionary once decried, overlooked and rejected. It is the most dynamic form and the most tragic form simultaneously. The most powerful forms of contemporary art as protest all attempt to take on embedded power structures that have permanently damaged the collective psyche. At the same time, they are always doing this hampered by the history of iconoclasm and its imposition of indirect speech and elusive forms, often mediated by “administrators of the creative” whose job it is to ally themselves with the inside and the outside simultaneously. Art as protest therefore has to skirt the boundary between art and something that cannot be easily be recognized as art. Permanently changing shape and restating the conditions of its production and reception. It is in exile while remaining within the social structures it speaks out against.

There is a strong strand in the thinking around contemporary art that it should reject forms of direct, didactic and dialectical forms of protest in favor of preserving an elusive subjectivity that offers potential to save the artistic persona and their products from outside discipline. This position exists to protect arts indirect complexity and suggests that many forms of art as protest are simple minded posturing. This specific situation can be reframed by rethinking artistic autonomy via the new forms of exile and dissidence that surround us today. People have arrived all over Europe with specific new histories and new experiences of exile and dissidence that affect them on a daily basis. Colonial traumas also find new expression in an endless matrix of exile and dissidence speaking to the past and recharging the present. We must keep rethinking the protection of the elusive persona of the contemporary artist and find new ways to include these complex new forms of exterior dissidence and internal exile by creating new contexts, structures and critical languages. This work has already begun in earnest biennales and sophisticated art institutions but has barely touched broader society. The invertion of arts relationship to protest, from subject to agent, is a recent one in terms of human history and its potential is always under attack from bounding structures that attempt to moderate and mediate it or co-opt and instrumentalize it. Reverse iconoclasm has the potential to introduce art into social and political spaces from which it has previously desired separation. Retaining relationships as they are today affords too much power to the mercantile, the institutional and the simple mindedly political. Reverse iconoclasm suggests it is time to take control of the distribution of images and objects on a structural level. To leave the designated spaces of art and take over the proliferation of images and contexts that are driven by algorithms, displaced capital flows and the insideous endurance of cultural repression.

Liam Gillick, 2022

First published in The Philosopher

Autumn 2022, Vol.110, No.4

Contemporary art and contemporary philosophy are bound together – like alchemy and religion. Martin Luther wrote, “The science of alchymy I like well, and, indeed, ‘tis the philosophy of the ancients.” All art produced in our time operates within terms of reference that have dominated the key strands of continental philosophy, even while understanding that the idea of continental philosophy is something of an uncomfortable construction. Contemporary art at the highest level, wherever it is made in the world today, derives it discursive models from a mixture of Frankfurt School critical theory, Freudianism, “Western Marxism,” and further more recent developments in post-structural theory, especially French ones. (It is also deeply affected by the esoteric movements of the nineteenth century that led to Rudolf Steiner, the Bauhaus, and forms of subjective humanist spiritualism, but that is for another text.) Written from the perspective of an artist working today, this short piece will suggest a quick abstract sequence of associations between art and philosophy, and the ways in which they feed each other. I will attempt to demonstrate this by looking at two extremes: “Artist A-+” and “Artist A+-”. While one attempts to deny the presence of a philosophical context, the other yearns for it.

“Artist A-+” claims to be outside of the influence and conscious application of contemporary philosophy. Let’s imagine that their work is super-subjective, i.e., it only expresses that which the artist intuitively feels as an ideal, if flawed, expression of their own art language, within their own terms and not derived from any outside conceptual models or subject to any judgment. Maybe, like Duchamp, they prefer to think of what they make as “an-art” rather than “anti-art”, meaning it thrives without the oxygen of art’s history or intellectual context, and therefore does not operate against it either. Yet “Artist A-+” is not in fact operating outside of philosophy, as their approach is already accounted for in philosophy. The “outsideness” of their conceptual model is a conceptual model. The way they describe their own condition of exteriority from discourse is, in fact, borrowed from philosophical writing about the place of creativity within theories of aesthetics. “Artist A-+” also has a further problem to address: as soon as their work is out in the world, the artist who claims to be outside of philosophical discourse cannot escape the fact that the analytical and critical terms brought to bear upon their work emerges from philosophy of the contemporary period, which itself provides the discursive base of contemporary art criticism.

“Artist A+-” is also working today and carefully follows the “correct” journals, conferences, and varied published materials produced by philosophers. Despite appearances, and against their desires, however, they are not in fact operating within philosophy but are always kept away by their own self-nomination as “a contemporary artist”; they are only able to reach in and out to find areas of interest and suggest routes towards philosophical understanding from a deterritorialized outlandish position. The artist attempting to operate within philosophy is an alchemist, boiling up contemporary philosophy in a laboratory of desire, throwing references, images, and structures into the brew in an attempt to walk alongside philosophy, while at the same time carrying an increasingly unwieldy baggage of video projectors, artist’s statements, installations, and propositions. “Artist A+-” cannot reach a condition where they are fully operating within philosophy. This is because they cannot fully enter the territory of philosophy without giving up the condition of endlessly becoming an artist.

This contradiction between the “Artist A-+” wanting to be outside and being pulled in, and “Artist A+-” wanting to be inside and being permanently self-excluded, is where contemporary art gets its tension and its staying power. The difficulty in pinning down contemporary art is due to the paradoxical condition of its producers, who both exist simultaneously inside and outside of philosophy. Despite their best efforts, there is an endless pull towards philosophy for “Artist A-+” and an alienation from it for “Artist A+-”.

A contemporary artist is a creative human who is always operating within and without philosophy, while also operating alongside all the other artists who are likewise in the same situation – whether they like it or not. All of them are making art towards the idea that they will continue becoming an artist. Every art work is incomplete evidence of the continued intention to become an artist. “Artist A-+” and “Artist A+-” are both committed to the endless process of crossing an unknown mountain range where scaling one peak only reveals further peaks beyond. Without this, they would not be endlessly becoming an artist and there would be no art to make. Philosophy can offer a path through the mountain range, but the difficulty of following it would also remove the view of the mountains to come and therefore delete all the art to be made in the future. Even if “Artist A+-” were to follow one of the often contradictory paths offered by philosophy, in order to continue being an artist they would be doomed to keep pointing to the paths while repeating the assertion that the mountains exist too, as the paths must lead somewhere. A lot of the confusion around contemporary art is down to this “pointing towards paths”. And it also explains why a lot of art today is based on super-subjectivity, systems, distancing devices, new technology, and non-traditional forms, e.g., art as identification, art as education, art as collective action, art as research, and so on. These forms of contemporary art practice all exist within the same mountain range as “Artist A-+” and “Artist A+-”, yet they tend to focus upon a maze of criss-crossing paths. The tension between the guiding path and a creative terrain is where the endless unresolvability of contemporary art gets its endurance.

The claims for legitimacy and potential within contemporary art in broader society derive entirely from the historic role visual art played in the modernist period – meaning that contemporary art still feeds off the codes and credibility of art established in the early twentieth century modernism. Visual art ran in parallel to the drive of technology, development, and various forms of growth. This growth included population increases, the trajectory of science, and human-centered conceptions of agency and self-perception expressed technologically. Modernism in art offered a precise critique of the position of visual culture in relation to concepts of what it meant to be human in a technological age. Every art form that was and is a denial of the trajectory of modernity is also a reaction to it. Art’s role during this period was not to be straightforward or comforting, nor was it meant merely to upset the bourgeoisie. Rather, it was to create a fragmented mirror of social, political, and cultural developments enacted by the drive of modernity. Modernism and contemporary art is the critical double of modernity. At times during the past 120 years or so, these twin trajectories came close, moved apart, and approached each other again.

It is this meandering ebb and flow of the aesthetics of trajectory confronted by creativity as the production of “art as art” – and not by accident – that gives us some inkling of the peculiar relationship between contemporary art and philosophy. It is by looking at how each area both created and then enacted theories of the mechanisms of our changing relationship to the recent past and near future that we find a common ground where we might still perceive the mountains and create new paths simultaneously. It is this endless unresolvability that sustains art and philosophy’s peculiar accommodation to each other in our time.

Organizational Pathways Restated

Liam Gillick, 2019

First published in Curating After the Global: Roadmaps for the Present, Eds. Paul O’Neill, Simon Sheikh, Lucy Steeds, Mick Wilson, LUMA, CCS Bard, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2019

Things should remain out of sync.

The edge should be perceived from the inside and outside simultaneously.

The idea of boundary pushing should remain.

Some things should be free.

There should be more difference.

There should still be a studio question.

There should be big sheds.

There should be a sense an activity remains to be defined.

Delusion should remain.

The question should remain “What kind of space are we in?”

A sense of the historically determined quality of decision-making and conditional relations should increase over time.

There should be an attack on pragmatism.

There should be a deep questioning of how choice is determined.

This should remain an incomplete project.

There should be the possibility of collective action.

There should be citizen artists.

There should be no form of social engineering.

There should be fresh springs.

There should be a sense that there is less structure.

There should be de-alienated labor.

There should be increasing proximity.

There should be new protective systems.

Some things should be more mobile.

Some people should be more migratory.

Some effects should remain local.

There should still be a feeling that there is a problem of vacuum.

Ideas should remain de-territorialized.

Some structures should disintegrate.

There should be fewer clear representations of power.

There should be the possibility of an architecture that expresses relationships. There should be an end to the idea that architecture is loaded with connections to the future.

There should be an increasing skepticism about architecture as an independent discipline.

There should still be a building.

There should be a sense that we are experiencing an excess of history from the first day.

It should be necessary to welcome parasitical structures.

There should be no equilibrium.

Other power structures should be mimicked.

There should be an increasing exposure of power and dynamics.

Who we are should keep expanding.

Some people should wonder how the future be stopped, or hindered.

There should be a reduction of appropriateness.

There should be an increase in duration.

Status should remain unclear.

Compositing should be used as a method of production.

The neighborhood should be a dominant model.

There should be an encouragement of non-directed energy.

There should be internal openness combined with public skepticism.

Water should become the most popular meeting place.

Some people should dream of the creation of an honest nostalgia.

There should be many spaces that produce incomprehension.

Role playing should be encouraged.

Repetition should be impossible.

Confrontation with past desires should be accepted.

New relationships should produce new understandings of obligations.

Personal relationships should multiply.

Claustrophobia should not exist.

Gaps in between shallowness and repetition should expand.

The institution should declare its politics.

Collectivity should be assumed.

No mission statements should exist.

Overlaps should be accepted.

Beta-testing of rights should become the norm.

Who is responsible should be the question every day.

Cultural sensitivity should increase.

Dispersal should endure.

Open access should be the cause of many arguments.

Medical centers should proliferate.

There should be no institutional furniture.

There should be custom databases.

Varied speeds of production should cause arguments.

Suspended judgment should no longer be a defense.

Interest from others should be a source of contentment.

Continuing regardless should be viewed as a crime.

Abuse of space should be encouraged.

It should feel as if unicorns are about to appear.

Orchards should bloom.

Economic growth should be suspended.

A department of rhetoric and announcements should not hold people back.

No one should feel qualified to develop a curriculum.

Secondary production should be encouraged.

An infinite number of departments should be established.

Places to play music should be maintained and well-loved.

The removal of the logo from the jacket should not be a dream.

Instant mythology should flourish.

The question of when should things finish should become a distant memory? Traces of journeys should be etched into our minds.

Gilles Chatelêt’s Devastating Prescience

Liam Gillick, 2019

First published in e-flux Journal #100, May 2019

...the whole problem consists in anticipating the anticipations of others, in singularizing oneself by imitating everyone before everyone else does, in guessing the ‘equilibria’ that will emerge from cyberpsychodramas played out on a global scale.[1]

In July 1998 I produced an exhibition at the Villa Arson in Nice with the deliberately unspeakable title: “Post Discussion Revision Zone #1 - #4 Big Conference Centre 22nd Floor Wall Design.” The exhibition comprised the removal of all the temporary walls from the main exhibition space of the Villa and the execution of a large geometric spiral wall painting in orange and brown on two walls. At each corner of the room hung a “discussion platform”: a 240cm x 240cm framework of anodized aluminum with transparent orange and light blue Plexiglas. People walking into this large space— 400sq metres — gravitated towards the “discussion platforms” and tended to gather under them surrounded by the deliberately a-profound graphic resembling the Ancient Greek meander motif. Visitors tended not to look at the work or necessarily talk to each other. They were perfectly alone-together in a zone preordained for some kind of enforced exchange.

The entire structure of the exhibition in Nice was intended as a soft-warning on the question of who controls the center ground of social and political life in a post-revolutionary program of developed postmodern consensus. It was one of many mise-en-scenes realized in exhibitions and collaborative projects between 1995 and 2000 that I initially referred to as What If? Scenarios in exhibition titles and associated texts. The term was a self-conscious parody of the new applied post-modernism of rebranding and future speculation as business model. The earliest exhibition structures were in advance of the publication of a book provisionally titled Discussion Island - Big Conference Centre (Orchard Gallery, Derry/Kunstverein Ludwigsburg 1998). The book was in the form of a speculative fiction set in the near future where three characters negotiate endless rebranding, conciliation, compromise and discursive subjectivity all taking place in highly designed non-places of pseudo exchange. At the outset - the draft of the book suffered the same problems as a great deal of speculative fiction in that it had no convincing location for action - rather the characters were stuck describing their conditions to each other - in the manner of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward or B.F. Skinner’s Walden 2. The exhibition structures - such as the one at the Villa Arson - were developed in order to provide a concrete series of settings for the book. The mise-en-scenes functioning as providers of an aesthetic prior to analysis and detailed action - something that could be described and acted upon with an awareness of a certain cinematic aspect where the setting itself can drive a narrative. This deliberate switching of cause and effect, point of reference and analysis was intended to find an aesthetic frame for a state of affairs increasingly subject to rapid inversions of value and meaning. This was a period of rapid rebranding - new Ancient Greek sounding names appearing within ambient ambivalent spaces of exchange as a replacement for more difficult and directly contestable activities or scandals. Altria, Aga, Areva, Avaya, Aviva, Capitalia, Centrica, Consignia, and Dexia were joined by Acambis, Acordis, Altadis, Aventis, Elementis, Enodis, and Invensys. By 2001 Arthur Anderson Accounting had become Accenture and Philip Morris has rebranded as Altria - all in an attempt to reflect the potential of the new Global markets and unforeseen opportunities, all carried by new names that could be associated with visual affects spinning free from concrete associations.

The first line of Discussion Island - Big Conference Centre set the scene. A new space of Conference Centres, rebranding and aesthetic misdirection masking trauma and pain:

However hard you try it’s always tomorrow. And now it’s here again. Across the other side of town trauma had overwhelmed personal exchange. Something self-willed and determined had cut through the dusk. Pain in a building. We all called it The Big Conference Centre.[2]

My 90s-era depiction of a world of endlessly mediated exchanges did not propose an origin or a series of didactic or documentary paper-trails. It only pointed forwards. I needed new tools to to understand the location of a starting point. Standard postmodern accounts of contemporary art seemed insufficient to cope with the ravages of the Thatcher and Reagan period during the 1980s and 1990s - to a young person the writing seemed too formalist and overly obsessed with signs, signifiers, irony and allegory - a bit like a Homeopathic Emergency Room trying to cope with the mass arrival of victims of a bus that had been driven off a cliff. There was a widening gap between the traditional art exhibition as a form and its newly emerging critical double – the product of curator(s) working alongside the artist to investigate the possibility of a new form of exhibition that questioned all aspects of display, mediation, experience and communication . A sequence of projections, situations and “films in real time” were produced by a number of artists at this time in an attempt to realize the near-future aesthetic conditions - Philippe Parreno and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster were certainly convinced of this new cinematic affect in the early 1990s. This was an effort to aid and offer structural support to collapsing models of resistance and collectivity that were being outmaneuvered, picked off and co-opted by the accelerated rebranding and blurring of corporate and public life following a period of rapid capitulation and rebranding. It was not an attempt to replace more urgent direct action or political urgency but to make a contribution by taking apart the aesthetic framework of the new neo-liberal concensus. Was there any way to deal with the semiotic calamities of the years since 1968 other than via self-conscious reference to the various failures of applied modernism and their imminent co-option? One option was to at least unveil the deceit at the heart of the new belief in “transparency”.

Looking back into that period from the present, it would have been useful to know the writings of Gilles Chatêlet at the time. He only appeared to me recently in a footnote on page 225 of the book 30 Years: Les Immateriaux edited by Yuk Hui and Andreas Broeckmann. There it was. “See G.Châtelet,To Live and Think Like Pigs: The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, trans.R.Mackay (Falmouth and NewYork: Urbanomic and SequencePress, 2014). What the hell was this book with such a great title? And how had I missed it? It would prove - in part - to offer some of the essayistic and fantastical accounting of the period between 1968 and 1998 that I had been missing and that had not been effectively accounted for in earlier attempts to shoehorn the new self-conscious post-modern art practices into their various allegorical and ironic frames.

“To Live and Think Like Pigs”[3] was published in Paris by Gallimard in 1998 but did not appear in English until 2014.[4] The first chapter of the book is set in 1979, twenty years before its publication; now we are twenty years on from the point it was first published in French. These twenty-year jumps offer distinct periods – in terms of technology, the social, and the constitution of shifting mainstream political constellations. The twenty-year step offers identifiable indicators and markers of the social and its bounds that identify points of change more effectively than thinking in terms of decades. Twenty years is enough time to understand the development of a new technology through to its application. Twenty years is enough time for a new educational models to take effect - both negatively and positively. Twenty years is still enough time to wonder whether a set of ideas within the art context retains any relevance or needs re-consideration. Twenty years was also the basis of earlier avant-garde promises and speculations. Maybe an artwork only has a limited lifespan. It is for this reason that Duchamp believed that an artwork should only have a twenty-year lifespan.[5] In the same interview however, Duchamp asserts that language in the form of literature lasts longer as it takes longer to mutate - this statement is clearly open to contestation as we become more conscious of linguistic power structures - yet the provocation and its implications about art and its value over time remains under quoted and resonates for me here. It is maybe the reason why my entire project at the time circled around a yet to be written book that would be exchanged cheaply and easily under the guise of a novel.

“To Live and Think Like Pigs” is an account of two dominant ideas from the 1990s that have now, two and three decades later, become markers of crypto-freedom in the hands of global data boys and have led to tragic inequalities of movement. It is a book against the way Chaos Theory, nomadism and anemic under-developed concepts of difference were used throughout the 1990s as an enlightening model – and against poorly deployed mathematics-as-theory in general. “To Live and Think Like Pigs” is an account against this nomadism that appeared a liberatory metaphor at the end of the twentieth century, yet in the twenty-first has become a dominant model of the cultural class in permanent motion and a growing underclass penned and restrained. It is a book against the “rational” individual as human data unit. It is against the political “market”. It is against the self-policing of all aspects in life. It predicts the envy culture of “Rhinoceros psychologies and reservoirs of the imaginary for the pack leaders of mass individualism.[6]” And roundly mocks them. And in doing so he also roundly mocks our 2019.

A late chapter is titled “The Fordism of Hate and the Resentment Industry”. What a perfect heading for the diminished social fabric of our time. The creation of a permanent underclass. The shift of resources and capital from poor to rich. The isolation and abuse of those who do not conform to standard models, and most importantly the acceleration of technological surveillance under a voluntary code of data submission and self-policing:

The Gardeners of the Creative had basically sought to play Nietzsche against Hegel, and often against Marx. But they had chosen the wrong target: it is neither Hegel’s owl nor Marx’s mole, nor Nietzsche’s camel that surprises us at the turn in the road: it is Malthus, peddler of the most nefarious conservatisms, always smiling and affable, who stands watching the suckers haggling over the libertarian gimcrackery of nomadism and chaotizing[7].

Let it be understood, first of all, that I have nothing against the pig…

Thus begins Chatelet’s preface. The book itself opens in a nightclub. It is a Sunday night in November 1979 and “no one” who claimed to be anyone “wanted to miss The Night of Red and Gold.”[8] A specific set of characters who appear to be all male and all in control of some aspect of their lives, have come together. The Four Tuxedos and The Cyber-Wolves are key players among a “pool of beautiful, available, and arrogant suburban hounds[9]”. All of these well-dressed hounds and wolves are hosted by nightclub “master of ceremonies” Fabrice and his “truculent collaborator,[10]” The Glutton. Fabrice is our witness and the one who can see what is taking place while not gauging the full impart of the moment. Even so: “he could sense how unstable was the cocktail of Money, Talent and the Press—as finely poised as the physicist’s famous critical point where gaseous, liquid, and solid states coexist.”

The opening scenario at the club’s Night of Red and Gold in ’79 points us towards our current conditions of exchange. It is a place of display and anxiety where tensions are overwritten by a collective signaling of potential and progress masked by new lifestyle allegiances. As Gilles Chatêlet wrote in a 1998 interview:

It’s a book about the fabrication of individuals who operate a soft censorship of themselves; on the construction of what I call yoghurt-makers, of which Singapore is the typical example. In them, humanity is reduced to a bubble of rights, not going beyond strict biological functions of the yum-yum-fart type…as well as the vroom-vroom and beep-beep of cybernetics and the suburbs (the function of communication). [11]

Typical of the book this section needs reading a few times for the vitriol to settle. Is he condemning the new City States of Globalisation? Absolutely. Is he questioning the emergence of a new virtue-signaling isolated to the privileged and a-profound? From our perspective there might be troubling implications here but I do not believe he is going against real change and difference but rather a new constellation of eco-consciousness driven by the what would become the mature internet. It’s a snobby section but an important one to indicate a new nationalistic form of development - the artisinal and the local powered by devices making claims for freedom that will not be able to fight off the self-censorship that will ensue. All this is achieved within a text that is raw, sharp and unleashed to the point where we are eventually dragged through a towering spiral of argument that slashes wildly at the emergent “realism” of the late post-modern consensus:

Pathetic young snobs trying to keep afloat in what already could only be called post-leftism! ... with their ‘let’s not kid ourselves’, their ‘it really resonates with me’, and above all their ‘in my opinion, personally…[12]

…that ‘singular beast’ with the subtle snout, certainly more refined than we are in matters of touch and smell…

I want to focus on this nightclub. The subtitle of the book is “The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies”. This is the site where the emerging class of super-self-conscious agents of narcissism are first introduced to each other in advance of their ultimate collective dividualization and envy laden accommodation within the neo-liberal “counter-reformation.”

Taking us clubbing, just ten years after the uprisings of 1968, places the conditions of envy and boredom in a pre-digital zone where people still come together yet are already rehearsing their role as “gardeners of the creative[13]”. The high-class Tuxedos are confronted by the pioneers of a forthcoming digital age. The shared work spaces and digitally shared envy-loathing of our present are pre-formed yet still surrounded by a protective bubble of excessive and hedonistic expectation.

The club is the setting - it is not the cause. It is the place that is open to identifiable proto-groupings - not only the Tuxedos and the Cyber-Wolves but the whole mix of a nightclub, from suburbanites to bankers, and opportunists who congeal in a lush swarm that pounds its way through the night. This is a particularly French nightclub of the 1970s.Emerging in parallel to those New York but with an inter-class tradition of its own - even if a certain group of international celebrities attended both - from Warhol to Jerry Hall, and Serge Gainsbourg- a combination of the faded aristocracy, the political operative, the suburban party people, and the emerging new entrepreneurs of the self. In the words of Fabrice:

“...anyone who had not known the end of the 70s would not have known the sweetness of life, the thrill of this seesaw where History teeters between an old regime and the roar of a Revolution.”

The role of the club here is doubled and complex. It is the site of initial recognition across the crowd of the twinned drivers of the hyper-malaise to come - the Tuxedos and the Cyber-Wolves – the jaded pseudo-bourgeoisie and the energized proto-digitalists. At the same time it is still peopled by a mass of hedonistic potential that is driving and plenishing master of ceremonies Fabrice - for he is still excited by this blending on the nightclub floor: “Shouldn’t a Prince of the Night be capable of making age groups, generations and social categories bear fruit by interbreeding them and seminating them with looks...? (IBID.) ”

But let it be understood also that I hate the gluttony of the ‘formal urban middle class’ of the postindustrial era…

From 1969 Chatêlet was an activist in the Front Homosexuel dAction Revolutionnaire (FHAR). The group denounced “fascist sexual normality”, “sexual racism” and “hetero-cops” who enforced the sexual status quo”[14]

A revolutionary movement founded in 1968, FHAR offered new forms of resistance to the dominant culture - including the hetero-normativity of the traditional and revolutionary leadership on every front of the left. In tracing “The Spirit of May ’68 and the Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement in France,” Michael Sibalis relays official French Communist pathologizing brand of homophobia:

Jacques Duclos, Secretary of the French Communist Party, once upbraided FHAR militants: "You pederasts - where do you get the nerve to come and question us? Go get treatment. The French Communist Party is healthy!” Trade Unionists, Socialists, Communists, Maoists, or Trotskyists all looked askance at the Gay liberationists from the FHAR who joined their annual May Day march in 1971.”[15]

FHAR members found political urgency by scandalizing both the bourgeoisie and the North African Arab areas of Paris - turning up in high-class places such as Café Flore as often as they appeared at the cafeterias of the Banlieue – dressed in “bathing suits and tottering on high heels with hair on our legs”[16]. By the mid-70s Chatêlet was drawn towards the explosion of new gay clubs in Paris - starting along in Rue Sainte-Anne in mid-70s[17]. This means the book is part autobiography - or more precisely it draws upon Chatelet’s own observations of the nightclub as a location for ideological promiscuity and display. The tone of the chapter implies frustration, cynicism and wonder in equal measure. It is quite possible that Chatêlet would have known or encountered precise examples of his Tuxedos and Cyber-Wolves on his nights out. At the same time he appears to be suggesting his own role as an implicated player in the nightclub as incubator of a new heterogeneity capable of being lured into a collective malaise of the future digital world of envy and boredom.

While the remainder of the book focuses upon the broad erosion of revolutionary potential and the suffocating effects of neo-liberalism, the decision to situate the opening chapter in a club is significant and written from this self-lacerating experience. Mohammed Salemy asserts in his “Intro to Chatêlet”[18] that:

Alongside his life as a scientist and an intellectual, Châtelet lived another as an unchaste party animal and, according to friends, was a fixture at La Palace, Paris’ response to New York’s Studio 54 and the allegorical setting of the book’s first chapter.[19]

The nightclub is filled with “...young condottieri of fashion, predators and headhunters... unforgiving to puppets who dare invoke any social hierarchy whatsoever.[20]” Anyone can be a citizen of the night. Among the crowd Fabrice can spot The Tuxedos, “...those who can hold aloft three generations of elegant parasitism... [21]” But from the moment we first encounter the Tuxedos it is clear that something has changed and they no longer retain their class privilege and clear status. Although we meet them without any backstory or context it is clear that they are becoming aware of their performative role, through which “finally they could adopt the modest, defeated tone of celebrities who, yielding to the crowd, had agreed to remove their disguises.[22]”

On a couch opposite the Tuxedos sit the Cyber-Wolves. Fabrice and The Glutton stand aside and comment on their mocking exchanges. This is the meeting of those threatened by the new constitution of the night - with its dangerous mix of classes and identities, and those who see opportunity in an incipient emergence of dividual desire and the banality of contemporary politics at the expense of combative revolutionary potential.

The neoliberal Counter-Reformation... would furnish the classic services of the reactionary option, delivering a social alchemy to forge a political force out of everything that a middle class invariably ends up exuding—fear, envy, and conformity.[23]

The Cyber-Wolves are the embryonic new-tech power class - they are a deluded group of preening arrogant nerds easily crushed by the Tuxedos in a last gasp battle of class expression: “The Cyber Wolves, a quartet of young pedants prey to every trend... so many other suckers, the great goofballs of the cyber-pack thought of themselves as princes of networks and tipping points[24]” The evangelists for new technology. Those who promised a connected world to come where technology would contribute to the end of history and difference. Technological “amplification” would provide a universal market of the self and networks would allow the financial market to regulate itself.

It is at this point that Chatêlet embarks on his turbulent narrative that boils over the rest of the book - each chapter addressing a different aspect of the implications he has laid out in the club but still punctuated with turns of phrase with regurgitated and twisted points of reference and ideas that catch the unwary reader more used to a smooth flow and uninterrupted thesis. For Chatêlet it is clear which way the initial nightclub exchanges are heading. The Cyber-Wolves and the Tuxedos along with Fabrice have been sucked into the eye of a coming storm. Partly thanks to the boredom and weariness of the former revolutionary thinkers, they are roundly losing their resistance and are about to be launched into the 1980s with its effective and traumatic application of a counter-revolution of devastating power. “The reality check would come soon enough!” the narration reflects…

It took less than three years to dissipate the charm and to assure the triumph of the 80s, with their nauseating ennui, greed and stupidity, the years of neoliberal ‘conservative revolutions’, the cynical years of Reagan and Thatcher. [25]

Three key philosophical aspects from the time are opened up and gutted by Chatêlet’s acid prose: Difference, nomadism and the attempt to play Nietzsche against Hegel and Marx. For him it is the anti-dialectical aspect of these three applications that render them capable of being so effectively co-opted, marketized and manipulated. Torn out of a critical context these constructions can enter into an effective interplay with applied individualistic political theory and made subject to increasing market-based super-subjective misdirection. The book from this point on is a poison pen letter to his contemporary intellectuals and mathematicians. It is a confession of having been witness to its birth of the conditions that directed consumption towards the self.

“To Live and Think Like Pigs” is about the marketization of every gesture - made possible by the accommodations that were made between increasingly cynical class actors at every level in cahoots with an emerging the Ayn Randish pseudo-ethical nerd culture that would come to feed on the individual as a source of data under a flag personal liberty maintained by envy and incited by boredom. Following our night in the club, an irreversible change has been set in place. The complete and utter capitulation to “rational expectations”:

“Now would come the era of the market’s Invisible Hand, which dons no kid gloves in order to starve and crush silently,[26]”

While a surprising success in France the book was unavailable in English and has become somewhat overlooked. If we had been more aware of it outside of the Francophone context then the anger and complexity of Chatelet’s devastating run through of the origins of our condition would have fed us with frightening clarify and precision for what was to come. My account missed the narcissism, nationalism and collapse that has become a perverse conclusion of the neo-liberal counter-reformation begun by Friedman et al – enacted by Thatcher-Reagan – and now conclusively pantomimed by Trump and the hysterically fabulist Global strong men of 2019 and their all too real and shocking new forms of nationalism. There would also have been less bad group shows about Nomadism and Chaos theory. A nightclub standoff between a weary aspirant consumer class and a group of Cyber-Wolves would have been a good astringent.

At the end of Discussion Island - Big Conference Centre - a book of rather meandering mise-en-scenes – a man suddenly jumps out of the Big Conference Center window, landing on top of a Toyota. It is unclear whether the person has fallen, jumped or been pushed. What I do know is that it seemed crucial to include this scene to indicate what I could not account for in the text. I may have been thinking of Deleuze or Debord, both of whom had recently taken their lives. Gilles Chatêlet committed suicide in June 1999 while suffering from AIDS, one year after the publication of his powerful and moving plea for everything to be better and different and unbound from the predations of envy and boredom.[27] I was not thinking of him.

[1] To Live and Think Like Pigs, The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, Urbanomic and Sequence Press, 2014

[2] Discussion Island: Big Conference Center, Derry, Orchard Gallery, Ludwigsburg, Kunstverein, 1998

[3] Vivre et penser comme des porcs. De l'incitation à l'envie et à l'ennui dans les démocraties-marchés. France: Gallimard, 1999

To Live and Think Like Pigs, The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, Urbanomic and Sequence Press, 2014

[4] In that year, Urbanomic released a translation in collaboration with Sequence Press.

[5] “There is life in a work of art which is short… even shorter than man’s lifetime. I call it twenty years. After twenty years an impressionist painting has ceased to be an impressionist painting because the material, the colour, the paint, has darkened so much, that it’s no more what the man did when he painted it. Alright. That’s one way of looking at it. So I applied this rule to all art – art works – and they after twenty years are finished, their life is over.” Duchamp interviewed by Richard Hamilton, London, 1959, Audio Arts Cassette, 1974, Tate, London.

[6] ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] To Live and Think Like Pigs, The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, Urbanomic and Sequence Press, 2014, 11.

[9] To Live and Think Like Pigs, The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, Urbanomic and Sequence Press, 2014, 14.

[10] Ibid, 13.

[11] Interview by Aquilès, Dr. No and Gros.

https://www.urbanomic.com/document/gilles-chatelet-mental-ecology/

[12] To Live and Think Like Pigs, The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, Urbanomic and Sequence Press, 2014

[13] ibid.

[14]. Gender and Sexuality in 1968: Transformative Politics in the Cultural Imagination, Editors: Frazier, L., Cohen, Deborah (Eds.), Berlin, Springer, 2009.

[15] Ibid, 245

[16] ibid.

[17] ibid.

[18] Intro to Chatêlet, Third Rail Quarterly, Spring 2015

[19] ibid.

[20] To Live and Think Like Pigs, The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies, Urbanomic and Sequence Press, 2014

[21] ibid.

[22] ibid.

[23]Ibid, 19.

[24] ibid.

[25] ibid.

[26] ibid.

[27] “He was particularly affected by the death of Gilles Deleuze. Wondering how not to give the suicide of the latter the sense of an ultimate and courageous revolt of life against the spirit of resignation and "laissez-faire". AIDS sufferer, Gilles Chatelet probably had the feeling to be facing the same challenge. He was 44 years old.” Marc Ragon, Mort du Philosophe Gilles Chatêlet, Libération, June 19, 1999.

Liam Gillick’s Discursive Topology

Nicolas Bourriaud, 2010

First published in One long walk… Two short piers… Kunst-und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, Snoeck Verlag.